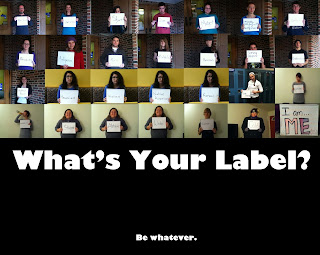

"This Is A Label" - a companion slideshow/film to my essay

Introduction

Coke. Pepsi. Bill Gates. Angelina Jolie. Nelson Mandela. Names

carry a significance that is comprised of generations of experiences,

reputation and effort. No two share a precise path of evolution, each

splintered and refracted by the experiences of the people living it. In the

language of rhetoric, names help us define the first and most essential of our

earliest discourse communities, our

families. In the tradition of familial closeness, language continues to assign

significance dependent on discourse communities differentiated by name. As

markers of these discourse communities, brands,

signs and labels help to define the boundaries of discourse communities by

identifying members and non-members and serving as conduits for inter-group

conflict. They allow for rivalries between companies to evolve into near

interpersonal feuds and help generations of cool (an uncool) high school

students decide who they can sit beside at lunch.

Brand Culture

Pictured above are two of the most vocal and powerful discourse communities in modern capitalism. Coke vs. Pepsi. The soda confrontation that defined a generation (or more). But more importantly, it manipulated the public’s opinion of not one but both companies by convincing their adoring fans that only one discourse community could come out on top. So, despite Coke having finally taken a substantial lead in the sugary soft-drink market, both companies brought in revenue in the billions, with additional profit coming from the numerous smaller companies and extensions each owns, such as FritoLay. But the effect of good-natured advertisements such as the ad on the right, put out by Pepsi Co. just in time for Halloween, is one of congenial mockery. Understanding exists, not only between Pepsi and Coke, but between the companies and their audience, that neither one is attacking their opponent company. Rather than a cavalcade of accusations and factoids about how horrible Coke is for your health, Pepsi fires shots on the very subculture of Coke, the people who believe with their very souls that Coke is genetically superior to Pepsi. They achieve a mirror of popular athletic discourse with this method, similar to the trash talking that occurs between sports fans (and infects Facebook in the weeks leading up to Cat/Griz). The "fans," as it were, rally to the defense of their product, Pepsi gets some press, Coke-fans on Reddit respond with a pithy ad of their own, and the world spins on.

But this result would not be conceivable without the polarizing effects of the all-powerful discourse community. Because, as the advertisements indicate, you are either pro-Pepsi or pro-Coke (unless you happen to be one of the godless heathens that claims they can't tell the difference, but those liars have no place in either discourse). By using their distinctive images as their primary polarizing weapon, Coke and Pepsi, like other famous - and infamous - brands, have used the formation of discourse communities to their advantage. This formation is the most superficial of all the discourse communities related to the psychology of labels, but it functions as an undeniable mainstay of American economy and society. Brands using discourse communities to foster a feeling of "sameness" between a large group of people use what Fish refers to as a "manipulation of reality," attributed to rhetorical man. This manipulation, intended as a criticism of the inability of rhetoric to unveil truth, instead functions as a low-level type of societal glue, keeping an advertising audience with few certain commonalities together.

[Great Rivalries of Our Times. Burger King vs. McDonalds and Apple vs. Microsoft.]

Signs, Significance

These are signs. They denote possession of a thing, brand a place,

person or item as the real or metaphorical property of an overarching agent –

in this case, the Montana State University Athletic Department. Signs are

abundant; all of the above and branding by a larger organization. It is clear,

concise and largely unremarkable (unless you like me, feel like going out of

your way to remark on it.) The false ownership that discourse communities feel

through brand preferences becomes a fully realized phenomenon in the signage of

our day to day lives. People love to literally label. We have a machine called

a label maker and we use it exactly as the name implies: put your name on your

belongings so everyone knows they're yours.

These are also signs. Unlike the personal sign, these denote

function and location and deal less with the possession of the labeled thing

and more with the location, function and necessity of the labeled object or

place.

What do these signs have in

common? All were photographed using and iPod. All live in the Brick Breeden

Fieldhouse. And all of them denote possession, pertaining to a group or

discourse community. According to Tania Murray Li, “anthropologists have

long acknowledged the social nature of property: that it is not a relationship

between people and things, but a relationship between people, embedded in a

cultural and moral framework, a particular vision of community” (Lee, 501-502).

Signs, as Li is quick to point out in the description, are easy to misconstrue.

They are, at first glance, a form of label, sure. That identification is

simple, plain and yet as inclusive as necessary. They explain. Who the thing

belongs to, what the things does, where the thing is. Signs are an analogue

communication web, passing information from writer to audience in an efficient

and simplistic manner. Signs fulfill a highly necessary function in the

formation of literal networks, bringing groups together in places for

functions, all denoted by symbols on a page. It is not until those symbols lose

their physical form that they endanger clear communication.

This Is A Label

This is a label. It looks a

little different than the examples above, but do not be deceived. This is the

personal label.

The personal label is most

similar to the signage of ownership, but it can be both self-assigned and

utilized as a personal version of the brand. In this way, it combines the most

effective strategies of the top two methods of labeling.

The personal label serves as the mating call of social

friendships, drawing geeks, nerds, jocks, preps and fangirls together across

huge social strata, such as large school or work settings.

Not all labels are self-assigned. When I first pitched this

project to the Digital Media class, I could see the blossoming horror on my

classmates' faces as they recalled terrible names from childhood classes. I

worked to make the video about more than name calling and hair pulling, because

the function of the personal label means so much more.

The personal label can be a connection into a societal network,

ready and waiting. Fangirls, a somewhat derogatory name from women madly

obsessed with a type of media, is also a word that has been joyfully reclaimed

by those it appears to exist to slight. To identify as a fangirl is, in many

ways, to accept the mantle and trappings of a label given to you by someone

else; and in making it your own also reinvent it.

The personal label can be a passing identification, a self-assured

title that denotes what you feel, think, or believe at a given time. It

broadcasts your emotion and communicates with others who also temporarily

occupy the same brief discourse. In this way, internet forums have achieved

enormous success by catering to the whimsical bitching needs of the multitudes

online.

Lastly, labels can be arbitrarily

assigned to you based on signs you express to the world at large. Short hair?

You're a lesbian. Well-dressed and polite? You're metrosexual at best, probably

gay. Tattoos and piercings? No good stoner.

These are the labels that harm

and constrain. They can help disenfranchised parties to form groups in defense,

but these groups are not high-functioning, collaborative discourses. The

resentment produced by this last construct of personal labels undoes any good

the labels themselves can enact, almost before it happens.

In Conclusion

People like judgement. It feed social situation and the gossip in all of us. And labels make gossip easy. Really, really easy. So easy, in fact, that people forget the function of labels as community. They forget the network that labels helped them build, the product it helped them sell, and the friends it helped them find. In an age where quotes are judged twice-over by their ability to condense into 140 characters or less, the complications of subterranean labels is not something the average human gossip machine wants to contemplate. So the discourse communities that we construct with the labels of our lives, the brands, the signs and the incessant name calling, culminate in an anticlimactic rush of information we feel compelled to simultaneously share and downplay the importance of.

Everyone is an individual. The trick is recognizing that everyone does not begin and end with you.

Everyone is an individual. The trick is recognizing that everyone does not begin and end with you.

Be whatever.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)